Tactile Maps

Overview

The project aims to improve indoor navigation for people with vision impairments, who often face challenges when navigating new environments. The goal is also to create a solution that not only benefits people with vision impairments but also enhances indoor navigation for everyone.

Problem Statement

Indoor navigation is a challenging task for individuals with vision impairments, particularly in environments with intricate pathways, indistinguishable corners, and an absence of guidance. The absence of a guide or map exacerbates this problem, making it increasingly problematic for people with blindness or low vision to navigate independently. Consequently, there is a crucial need to develop an effective solution that facilitates the indoor navigation of individuals with vision impairments, providing them with autonomy and freedom while enhancing their overall quality of life.

End User

The end-users for this project are primarily individuals with vision impairments who face challenges in navigating indoor environments. However, the solution developed through this project could benefit a broader audience, including new visitors to an unfamiliar location, individuals who struggle to remember directions, people with mobility challenges, and anyone who desires a more efficient and accessible way of navigating indoor spaces. Ultimately, the solution aims to enhance the overall experience of indoor navigation for everyone, regardless of their abilities or limitations

Collaborators

Themis Garcia, Dr. Amy Hurst, Gus Chalkias, Reginé Gilbert

Roles and Responsibilities

As the UX researcher, my primary responsibility was to conduct research and gather insights to understand the needs, challenges, and preferences of the end-users. I worked collaboratively with the team to translate these insights into actionable design requirements and ensure that the user's needs were at the forefront of the project.

I was also part of the Design process and worked with two other co-designers. I was responsible for creating the visual and tactile design of the indoor navigation solution.

This was a participatory research project and we worked closely and built the product with a co-designer who is blind.

Design Process

The project began with research to understand the challenges faced by visually impaired individuals in navigating indoor environments. The research involved interviews with Orientation and Mobility (O&M) specialists, evaluation of indoor navigation at NYU’s Ability Project facilities with O&M specialists, field research at The Helen Keller Services to research navigation in a space centered on the Blind and Low Vision community, and secondary research on indoor navigation, tactile maps, and spatial tracking

Empathize: The research helped identify the target users of the project, which were visually impaired individuals. We empathized with these users to understand their needs, challenges, and preferences in indoor navigation.

Define: The problem statement of the project was "Indoor navigation is difficult for someone with vision impairment, especially in places where there are confusing paths, similar-looking corners, and a lack of direction. This difficulty is amplified when a guide or map is unavailable, making it even harder for people with blindness or low vision to navigate independently.”

Ideate: The team explored different options to create a solution that was accessible and user-friendly. The team considered different sensory modalities, including tactility, sound, and fragrances. The team identified the use of tactile maps as the primary solution, with audio and visual layers to enhance the usability of the maps.

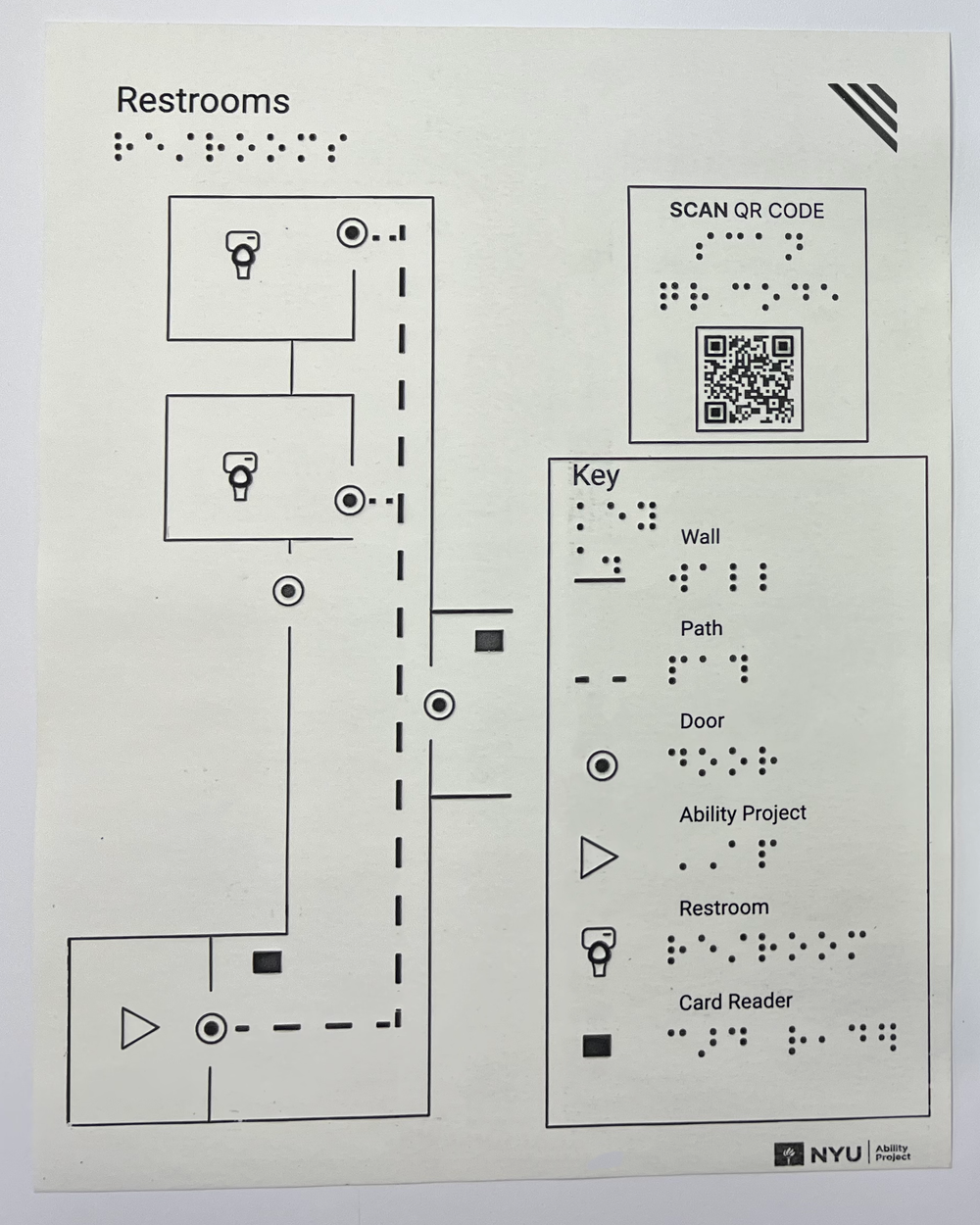

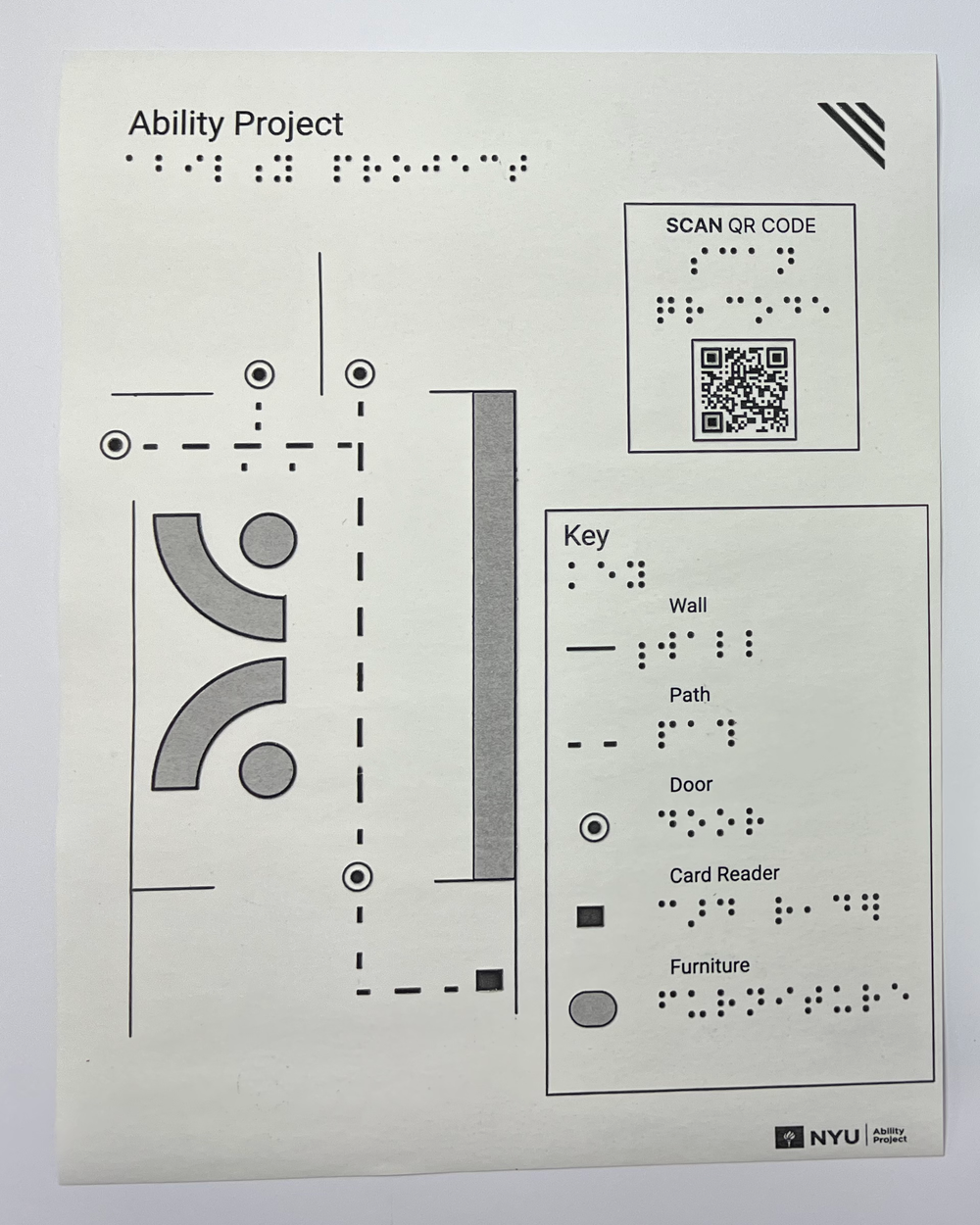

Prototype: The team created tactile maps using two layers of information: one includes the tactile material, and the second includes the visual details. The team used paper for the tactile printer method (Braille Embosser or Swell Form) and an ink printer for visual information only. This increased the usability of the maps, translated braille to text, added visual information, and reduced tactile clutter.

We also created a tactile symbol for a QR Code, which included its shape (a square) and its position markers. This tactile icon indicated the position, size, and orientation of the QR Code. Users located the QR Code to access a description of the tactile map using a screen reader on a smart device. The team chose screen reader technology over pre-recorded audio as it was more adaptable.

Test: The team tested the tactile maps with the target users and gathered feedback to iterate on the design. The team also tested the tactile QR Code and the screen reader technology to ensure that it was accessible and user-friendly.

Development: The team developed the final product, which included both tactile and visual layers, as well as the tactile QR Code. The product was designed to enhance the overall experience of indoor navigation for visually impaired individuals, ultimately making it easier for everyone.

This was an iterative participatory process. We kept making changes with our co-designers and experts from Helen Keller after every iteration. We also conducted in-person interviews in the end to test the maps.

Usability Test

Methodology: Participants were recruited through The Helen Keller Services and were included if they had a vision impairment that impacted their ability to navigate indoor environments. A total of 11 participants were included in the study, of which 6 were congenitally blind and 5 became blind over time. The study was conducted at NYU’s Ability Project facilities.

The study was conducted in two phases:

(1) Observational study of participants navigating the space without using the maps, and

(2) Usability testing of the tactile maps (Navigation after using the maps followed by Interviews).

In the observational study, participants were asked to navigate the space without using the maps, while researchers observed their movements and recorded the contact points, i.e., areas where they touched while moving. In the second phase, participants were provided with the tactile maps and asked to perform a few tasks in the space. They were asked to locate specific rooms, identify specific features, and navigate from one location to another. The maps were placed at different locations in the space, and participants were asked to provide feedback on the location that was most convenient and accessible.

A few open-ended questions that we asked the participants after they completed phase 2 of the study were:

What did you think of the tactile map? Did it provide you with the information you needed to navigate the space?

How did you find the braille display on the map? Was it easy to read and understand?

What was your experience with the QR code? Was it easy to locate and use?

Were there any features or information missing from the map that you would like to see added?

Is there anything about the design or layout of the map that could be improved to make it more accessible or user-friendly?

Overall, how would you rate your experience using the tactile map? Would you use it again in the future?

Can you describe any specific challenges or difficulties you encountered while using the tactile map?

Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience using the tactile map in this space?

Results: The observational study revealed that participants predominantly relied on touch and sound to navigate the space. Participants used the walls, door frames, and other structures as landmarks while moving. The tactile maps were effective in conveying information, and participants reported that the maps were helpful in orienting themselves in the space. The best location for placing the maps was identified as above the ID tapping station, which was accessible to all participants and did not obstruct the movement.

But we also found that not everybody can find the maps, in case they are visitors and they don’t need to tap their IDs, they will not go near that area because someone else will tap them in. Also, it is not a hundred percent certain that everyone who goes and taps their IDs will find the maps. So that led to development of another concept: The Navigation Guide. The Navigation Guide is an online repository of all the maps and information about maps that can be sent to expected visitors, so that they have an idea of the space before they actually come in.

Conclusion: Tactile maps can be a useful tool for indoor navigation for people with vision impairments. The study demonstrated that tactile maps were effective in conveying information and that the best location for placing the maps was above the ID tapping station. The findings of this study can be used to inform the development of tactile maps for indoor navigation in other settings. Further research is needed to evaluate the usability of tactile maps in other indoor environments.